THE CIVIL WAR STARTED IN DETROIT IN 1807, ABOLITION HISTORY AUTHOR CONTENDS

Motor City's Economic Comeback Shines International Spotlight on Michigan

August 2, 2017

By: Dave Rogers

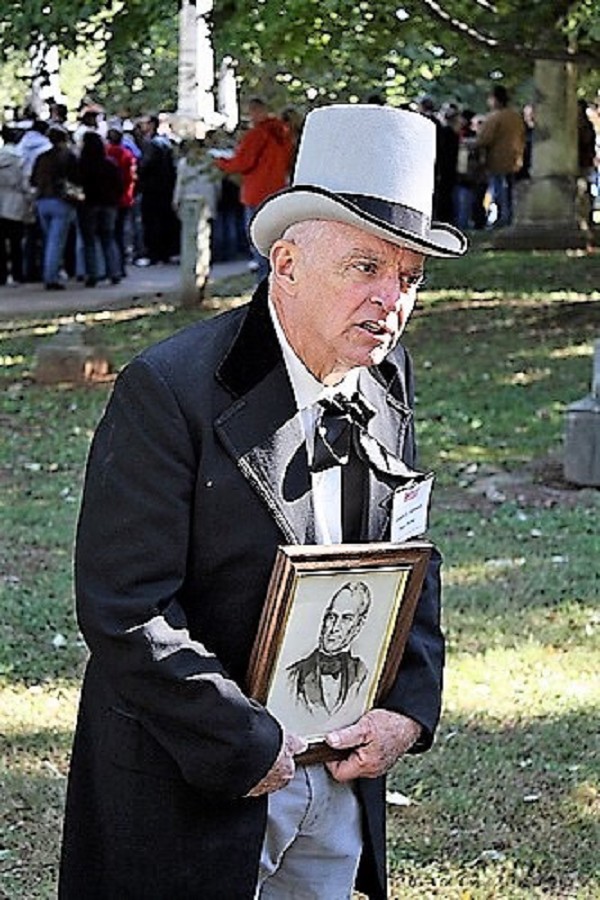

Topper Birney, great-great-grandson of James G. Birney, re-enacts the abolitionist leader (shown in photo) in a cemetery event in Huntsville, Alabama.

(AUTHOR'S NOTE: Periodically, as the United States continues its struggle for equality among all, it is instructive to review the facts of the conflict that have plagued us since the beginning of the Republic and the tortuous road to progress. The nation's racial dichotomy is no more evident than right here in Michigan. As Detroit is currently undergoing an amazing economic comeback, it is timely to recall the Motor City's admirable background as a wellspring of civil rights -- notable among Northern cities in the early 19th century, as well as its legacy of racial conflict.)

The roots of today's escalating class warfare nationally can be traced back more than two centuries, to Detroit of all places, where the first shots in the half-century run-up to the Civil War rang out, according to a mid-Michigan author.

And, for more than 100 years Detroit has also been the epicenter of a social divide that resulted in crashing smokestacks, debilitated neighborhoods and outright racial conflict culminating in the 1967 race riots.

"Of course Detroit for decades had been the main Northern terminus of the Underground Railroad, the escape route to freedom in Canada," said the author. "Today Detroit is a notable example of multi-racial, multi-ethnic cooperation that is finally fulfilling a more than a 300-year promise that began with its founding by the French explorer Cadillac in 1701. Detroit began its multi-ethnic legacy as Indians, Negroes, French, and English melded and built the city into a world automotive center."

Forbes Magazine recently commented: "In recent years, the city of Detroit, Michigan has earned the nickname 'America's Comeback City' -- and rightfully so. Detroit's unemployment rate dropped to 5.3 percent in 2016, down from a high of 19 percent. The poverty rate is now 13.4 percent, a full point below the national average. This transformation is proving that America's industrial cities can move forward and thrive as the economy evolves."

JP Morgan Chase commented: "In collaboration with the public sector, the city is rebuilding from the ground up, and revitalization is coming faster than anyone could have imagined when the city filed for bankruptcy in 2013."

This author documents the armed clashes in the mid-1840s between raiding Kentucky slaveholders and white abolitionists defending escaped slaves in Michigan's Wayne, Calhoun and Cass counties, concluding they ignited a political conflict that escalated to Civil War.

Actually, the earliest dispute over escaped slaves from Kentucky occurred in 1807 in Detroit, (about the time Lincoln was born) according to a 2011 book, "Apostles of Equality: The Birneys, the Republicans, and the Civil War," by D. Laurence Rogers, published by Michigan State University Press. When slaveholders tried to reclaim their bondsmen from Canada, freedom-loving white Michiganians threatened to tar and feather the judge who considered allowing their return.

Thus, the seeds of an egalitarian vs. aristocratic conflict that erupted in Civil War were planted more than half a century before guns roared at Fort Sumter.

Among the rabid abolitionists, William Lloyd Garrison was an anarchist and John Brown a terrorist, according to my analysis. Reformed slaveholder James G. Birney, a Kentucky and Alabama lawyer, offered a reasonable solution to the intersectional conflict. His philanthropic positions, aimed at changing the status quo on behalf of four million slaves, were soundly rejected by Northern voters in two runs for the Presidency on the Liberty Party ticket, the last while he was living in Bay City. However, his organizing in Michigan laid the foundation for the Free Soil and Republican parties.

Detroit, Ann Arbor and Jackson were centers of abolitionist sentiment. One notable entry in Birney's diary in the Clements Library at the University of Michigan is the observation that after the passage of the tougher Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 blacks poured through Detroit headed for Canada. Architect of that law, part of the Compromise of 1850, was Birney's nemesis Senator Henry Clay, his neighbor from Kentucky, a paragon of the Slave Power.

The influence of New England settlers, including Quakers, who often opposed slavery, was key to Detroit, and Michigan's, abolitionist leanings. They were imbued with the spirit of equality prevalent on the frontier and disliked Southern social stratification.

Other provocative insights and interpretations of the Civil War include:

Did the fact that Jefferson Davis barred enlistment of black troops doom the Confederacy?

This book contends that when the Confederate president rejected a general's idea to beef up decimated rebel forces, and Abe Lincoln approved black troops, the fate of the war was determined.

In 1864 the Irish volunteer Gen. Patrick Cleburne was roundly criticized, and denied promotion by Davis and other leading rebels, for his plan to enlist blacks and give them freedom.

The Union, on the other hand, welcomed about 186,000 blacks into the army -- about 10 percent of the entire force -- a factor believed by some observers to have tipped the balance in the conflict.

Both William Birney and David Bell Birney, who had lived in Bay City briefly, were major generals in the Union Army and played roles in recruiting and leading black troops.

William was one of the several recruiters of blacks for the Union, emptying jails in Baltimore and rescuing blacks from Maryland plantation owners to help build the Colored Troops, as then called, to a fighting force that some historians believe turned the tide in the bloody conflict.

During his research for the book, the author discovered correspondence in the National Archives between William Birney and President Lincoln as recruiting of blacks was underway that indicates the 16th President had strong abolitionist feelings -- mirroring those of Birney's father, James Gillespie Birney of two decades earlier.

Those roots ran back into Lincoln's youth. As a young man, on a flatboat trip to New Orleans, Lincoln saw the slave auction and was horrified, remarking: "If I ever get a chance at that thing (slavery), I'll hit it hard." The Apostles book author commented: "That was confirmation that deep within the heart and mind of the easy-going Lincoln lurked the soul of a reformer, much like James G. Birney, with an intense concern for his fellow man."

###