The Spirit of Dr. King on Saginaw's North Third Street in Summer 1977

Civic Activist Recalls Nonviolent Protest to Closing of Street

January 20, 2008

By: Guest Columnist

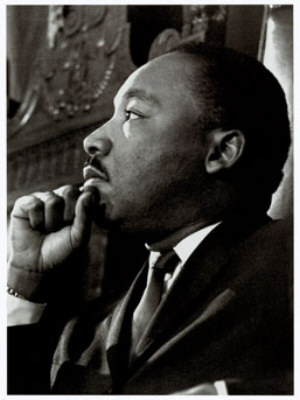

Martin Luther King

By a Saginaw Civic Activist

(Note to Readers: I have attended many Martin

Luther King Holiday events through the years, usually

speeches at luncheons. However, the event in my own

life that makes me most think of Dr. King took place

nearly 10 years before his holiday became official in

1986. I was doing community work, similar to what an

AmeriCorps volunteer would do today, in what I believe

was the spirit of Dr. King. Here's the story of what

happened.)

This is summer 1977 in Saginaw, and 40 urban

residents have gathered in late afternoon's warmth.

Many of them have folding lawn chairs, but this

is not the scene of a sunny picnic.

It's an inner-city picket.

Most of the neighbors are from 50 to 80 years

old. They are highly traditional and God-loving

people. In many of their homes I have seen framed

portraits of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,

often flanked by smaller images of John F. Kennedy on

one side and Robert F. Kennedy on the other.

The neighbors on this day are sitting and

standing on rutted railroad tracks where North Third

Street's narrow two lanes cross the edge of a C&O yard

that sprawls wider into the distance, into neglected

open acres of overgrown shoulder-high grass and weeds.

Businesses along the sides include a barber shop, a

shoeshine parlor, a poultry store, a bakery and a

corner grocery. Behind the scene is the massive Potter

Street Railroad Station, built of red brick in 1881

but now abandoned, which had been the portal for many

neighbors who arrived in Saginaw years ago from the

Deep South.

Saginaw City Council members and C&O plan to

close the Third Street traffic crossing at the tracks,

and residents are raising their objections in a

nonviolent and peaceful method that Dr. King may have

employed.

They have good reasons. Many streets in this

rundown area already are blocked either at the rail

yard or at the nearby Interstate 675, a new I-75

downtown business loop that bulldozed more than a

thousand homes and businesses and churches in the

heart of the East Side's minority community. By being

cut off from the rest of the city, the northeast

section's blight is becoming even more severe, and now

City Hall is approving yet another dead end. The rail

yard and the elevated highway are a scant three blocks

apart, like two Berlin Walls slicing through the same

ghetto.

Neighbors repeatedly have pleaded to keep Third

Street open. They have failed to reap a response from

city leaders and C&O. The summer protest on the tracks

is a last resort, just as the Montgomery bus boycott

was the last resort for a then-youthful Dr. King and

his followers.

Those lawn chairs accommodate the older

neighbors. Younger residents stand. Some in the group

chat with one another. Others are quiet amid the

tension.

A railroad foreman emerges. Enough is enough, he

tells the group. The trains need to run, and the next

one is coming through. Stay on the tracks at your own

risk.

The foreman pivots quickly, strides away and

makes a signal. A locomotive revs about a mile to the

east in the endless rail yard, back somewhere in the

depths near Fourteenth Street. The wheels squeal. Here

comes the chain of train cars, gradually building

speed.

Neighbors scatter aside off the tracks, lawn

chairs in tow. Even the oldest folks show an urgent

hop-skip-jump. They head toward the adjacent dirt

parking lot for Mama Lillie's, a soul food restaurant

in a tiny old brick hut.

But one of the younger protesters, Eugene

Henderson, is trembling with anger and refuses to

move. How can they do this? They're just gonna rev a

train and run over these mostly gray-haired people?

Where are the police? He stays glued on the tracks as

the train presses forward. Finally, a pair of the

older but still-strong men grab him and pull him back.

Three white people are part of the scene as the

train screams through: The railroad foreman. The train

conductor. And me, the shaggy young volunteer who is

the grassroots organizer of the black and brown elders

in the neighborhood association.

Afterward I ask myself, was it as close as it

looked? Would Eugene really have stood on those tracks

until the fatal end, lean and strong, crushed along

with his Coke-bottle eyeglasses?

This event is far from on a par with events

during Dr. King's era. It is not exactly a rival to

Alabama's 1963 Birmingham police dogs and fire hoses

and church bombings, or with the 1965 Selma

skull-crackings on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. But it is

equally as oppressive.

For Eugene Henderson and other neighbors, the

issue now goes beyond keeping a street open at the

railroad tracks. They once more feel racially

disrespected. This is nothing new, but at the same

time it never gets old. It always cuts to the soul.

(FOOTNOTE: The residents eventually lost their

fight for Third Street, but from 1976 to 1982 they

achieved grassroots victories in other ways to improve

neighborhood conditions. They cleaned abandoned lots

and took ownership of them. They helped repair homes.

They fought to keep schools and small businesses open.

I created the group but I didn't run it; they did. My

role was as their resource person. Many of the

neighbors had grown up in Jim Crow oppression that was

blatant in the Deep South, but that also existed up

here in Saginaw in a more subtle form. Through their

citizens' association they learned that they had the

rights to speak up for themselves, the same as any

other Americans. They treated me, as a young adult

making my door-to-door organizing rounds, like a

member of their own families. Most of them have passed

away by now, but their wisdom and strength and

kindness will always live within me. On this holiday I

honor not only Dr. King, but also these neighbors and

elder friends who lived and acted in his spirit.)###